|

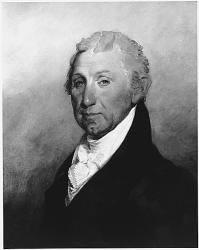

James Monroe - 5th President of the United States

James

Monroe (1758-1831), fifth president of the United States, was born on Monroe's

creek, a tributary of the Potomac river, in Westmoreland county, Virginia, on

the 28th of April 1758. His father, Spence Monroe, was of Scotch, and his mother,

Elizabeth Jones, was of Welsh descent. At the age of sixteen he entered the College

of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, but in 1776 he left college to take

part in the War for Independence. James

Monroe (1758-1831), fifth president of the United States, was born on Monroe's

creek, a tributary of the Potomac river, in Westmoreland county, Virginia, on

the 28th of April 1758. His father, Spence Monroe, was of Scotch, and his mother,

Elizabeth Jones, was of Welsh descent. At the age of sixteen he entered the College

of William and Mary, Williamsburg, Virginia, but in 1776 he left college to take

part in the War for Independence.

He enlisted in the Third Virginia regiment, in which he became a lieutenant,

and subsequently took part in the battles of Harlem Heights, White Plains, Trenton

(where he was wounded), Brandywine, Germantown, and Monmouth. In November 1777

he was appointed volunteer aide-de-camp to William Alexander ("Lord Stirling"),

with the rank of major, and thereby lost his rank in the Continental line; but

in the following year, at Washington's solicitation, he received a commission

as lieutenant-colonel in a new regiment to be raised in Virginia. In 1780 he began

the study of law under Thomas Jefferson, then governor of Virginia, and between

the two there developed an intimacy and a sympathy that had a powerful influence

upon Monroe's later career.

In 1782 he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, and though only

twenty-four years of age he was chosen a member of the governor's council. He

served in the Congress of the Confederation from 1783 to 1786 and was there conspicuous

for his vigorous insistence upon the right of the United States to the navigation

of the Mississippi River, and for his attempt, in. 1785, to secure for the weak

Congress the power to regulate commerce, in order to remove one of the great defects

in. the existing central government. On retiring from Congress he began the practice

of law at Fredericksburg, Virginia, was chosen a member of the Virginia House

of Delegates in 1787, and in 1788 was a member of the state convention which ratified

for Virginia the Federal constitution.

In 1790 he was elected to the United States senate to fill the vacancy caused

by the death of William Grayson, and although in this body he vigorously opposed

Washington's administration, Washington on the 27th of May 1794 nominated him

as minister to France. It was the hope of the administration that Monroe's well-known

French sympathies would secure for him a favourable reception, and that his appointment

would also conciliate the friends of France in the United States. His warm reception

in France and his enthusiastic Republicanism, however, displeased the Federalists

at home; he did nothing, moreover, to reconcile the French to the Jay treaty,

which they regarded as a violation of the French treaty of alliance of 1778 and

as a possible casus belli. The administration therefOre decided that he was unable

to represent his government properly and late in 1796 recalled him.

Monroe returned to America in the spring of 1797, and in the following December

published a defence of his course in a pamphlet of 500 pages entitled A View of

the Conduct of the Executive in the Foreign Affairs of the United States, and

printed in Philadelphia by Benjamin Franklin Bache (1769-1798). Washington seems

never to have forgiven Monroe for this, though Monroe's opinion of Washington

and Jay underwent a change in his later years.

In 1799 Monroe was chosen governor of Virginia and was twice re-elected, serving

until 1802. At this time there was much uneasiness in the United States as a result

of Spain's restoration of Louisiana to France by the secret treaty of San Ildefonso,

in October 1800; and the subsequent withdrawal of the "right of deposit"

at New Orleans by the Spanish intendant greatly increased this feeling and led

to much talk of war. Resolved upon peaceful measures, President Jefferson. in

January 1803 appointed Monroe envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary

to France to aid Robert R. Livingston, the resident minister, in obtaining by

purchase the territory at the mouth of the Mississippi, including the island of

New Orleans, and at the same time authorized him to co-operate with Charles Pinckney,

the minister at Madrid, in securing from Spain the cession of East and West Florida.

On the 18th of April Monroe was further commissioned as the regular minister to

Great Britain. He joined Livingston in Paris on the 12th of April, after the negotiations

were well under way; and the two ministers, on finding Napoleon willing to dispose

of the entire province of Louisiana, decided to exceed their instructions and

effect its purchase. Accordingly, on the 3oth of April, they signed a treaty and

two conventions, whereby France sold Louisiana to the United States.

In July 1803 Monroe left Paris and entered upon his duties in London; and in

the autumn of 1804 he proceeded to Madrid to assist Pinckney in his efforts to

secure the definition of the Louisiana boundaries and the acquisition of the Floridas.

After negotiating with Don Pedro de Cevallos, the Spanish minister of foreign

affairs, from January to May 1805, without success, Monroe returned to London

and resumed his negotiations, which had been interrupted by his journey to Spain,

concerning the impressment of American seamen and the seizure of American vessels.

As the British ministry was reluctant to discuss these vexed questions, little

progress was made, and in May 1806 Jefferson ordered William Pinkney of Maryland

to assist Monroe.

The British government appointed Lords Auckland and Holland as negotiators,

and the result of the deliberations was the treaty of the 31st of December 1806,

which contained no provision against impressments and provided no indemnity for

the seizure of goods and vessels. In passing over these matters Monroe and Pinkney

had disregarded their instructions, and Jefferson was so displeased with the treaty

that he refused to present it to the senate for ratification, and returned it

to England for revision. Just as the negotiations were re-opened, however, the

questions were further complicated and their settlement delayed by the attack

of the British ship Leopard upon the American frigate Chesapeake.

Monroe returned to the United States in December 1807, and was elected to the

Virginia House of Delegates in the spring of 1810. In the following winter he

was again chosen governor, serving from January to November 1811, and resigning

to become secretary of state under Madison, a position which he held until the

3rd of March 1817. The direction of foreign affairs in the troubled period immediately

preceding and during the second war with Great Britain thus devolved upon him.

On the 27th of September 1814, after the disaster of Bladensburg and the capture

of Washington by the British, he was appointed secretary of war to succeed General

John Armstrong, and discharged the duties of this office, in addition to those

of the state department, until March 1815.

In 1816 Monroe was chosen President of the United States; he received 183 electoral

votes, and Rufus King, his Federalist opponent, 34. In 1820 he was re-elected,

receiving all the electoral votes but one, which William Plumer (1759-1850) of

New Hampshire cast for John Quincy Adams, in order, it is said, that no one might

share with Washington the honour of a unanimous election.

The chief events of his administration, which has been called the "era

of good feeling, were the Seminole War (1817-18); the acquisition of the Floridas

from Spain (1819-21); the "Missouri Compromise (1820), by which the first

conflict over slavery under the constitution was peacefully adjusted; the veto

of the Cumberland Road Bill (1822)1 on constitutional grounds; and-most intimately

connected with Monroe's name-the enunciation in the presidential message of the

2nd of December 1823 of what has since been known as the Monroe Doctrine, which

has profoundly influenced the foreign policy of the United States.

On the expiration of his second term he retired to his home at Oak Hill, Loudoun

county, Virginia. In 1826 he became a regent of the University of Virginia, and

in 1829 was a member of the convention called to amend the state constitution.

Having neglected his private affairs and incurred large expenditures during his

missions to Europe, he experienced considerable pecuniary embarrassment in his

later years, and was compelled to ask Congress to reimburse him for his expenses

in the public service. Congress finally (in 1826) authorized the payment of $30,000

to him, and after his death appropriated a small amount for the purchase of his

papers from his heirs.

He died in New York City on the 4th of July 1831, while visiting his daughter,

Mrs Samuel L. Gouverneur. In 1858, the centennial year of his birth, his remains

were reinterred with impressive ceremonies at Richmond, Virginia. Jefferson, Madison,

John Quincy Adams, Calhoun, and Benton all speak loudly in Monroe's praise; but

he suffers by comparison with the greater statesmen of his time. Possessing none

of their brilliance, he had, nevertheless, to use the words of John Quincy Adams,

"a mind . . . sound in its ultimate judgments, and firm in its final conclusions."

Schouler points out that like Washington and Lincoln he was "conspicuous

. . . for patient considerateness to all sides."

Monroe was about six feet tall, but, being stoop-shouldered and rather ungainly

seemed less; his eyes, a greyish blue, were deep-set and kindly; his face was

delicate, naturally refined, and prematurely lined. The best-known portrait, that

by Vanderlyn, is in the New York City Hall. Monroe was married in 1786 to Elizabeth

Kortwright (1768-1830) of New York, and at his death was survived by two daughters.

Reference: Excerpts of the above history article are from the 1911 edition

Encyclopedia.

|